Friends,

One of the central challenges that the souls in Purgatory have to face is their changing relationships to their earthly allegiances, commitments, and loyalties, such as their kingdoms, cities, and families. On the one hand, they cannot help but retain real love and affection for (and sometimes resentment and frustration with) the places and the people whom they have left behind. On the other hand, they are on the same heavenward journey—albeit moving at their own individual pace—with others from very different backgrounds, including families and cities with whom they may have previously feuded and fought. Furthermore, their ultimate destiny is to be united with God and one another in joyful, open-hearted embrace.

Thus, the ties that interweave between the individual, the community, and the cosmos can be quite tricky to navigate! From ancient times, philosophers have postulated solutions to the problem of the one and the many; in contemporary ethics, debates between communitarians and cosmopolitans persist with regularity. One ancient figure who continues to inform both of these conversations—and who certainly influenced Dante-person in his purgatorial world-building—is Augustine of Hippo. In his Confessions, Augustine diagnosed the complex ways that love can make one out of the many. In his City of God, he envisioned two fundamental cosmopolitan communities: the City of Man (founded by Cain, ruled by Satan, and marked by vices like pride and envy) and the City of God (the true home of those who follow in the footsteps of Jesus, characterized by virtues like humility and self-giving love). This is what Sapia was referring to when she informed Dante that “each of us is citizen of one true city” (13.94-95), even as the rest of their conversation revealed the ways that she is still unlearning the habits of the City of Man.

As it turns out, this conversation has been overheard by others nearby. Such eavesdropping is hardly surprising, given that there is not much for these temporary sightless spirits to do, other than weep while repenting from the vice of envy and reflecting on the virtue of love. Today’s canto opens with a whispered discussion between two such shades (lines 1-6):

“Who is this man who circles our mountain

before death has given him flight,

and at his own will opens and covers his eyes?”

“I don’t know who he is, but I know that he’s not alone;

you ask him because you’re closer,

and greet him sweetly, so that he replies.”

The former speaker, who has not yet been named, does indeed turn toward Dante-pilgrim and ask him kindly to identify who he is, where he comes from, and what astonishing grace he has received. Dante’s response is a bit coy; he describes the river that runs near his birthplace without naming it, and he declines to disclose his name because “to tell you who I am would be to speak in vain—my name does not yet resound much” (20-21). This is an interesting dodge: is Dante, who typically is more than happy to exalt his own name, already trying to work on his own vice of pride? Is he denying that he is anyone worth envying, so as not to place a stumbling block in front of these souls that struggle with that particular sin? Is he trying to put the focus back on the speaker, from whom he hopes to learn? Or is he just misreading the moment and making things overly complicated?

Whatever the case may be, both of his conversation partners figure out that he is indicating the Arno River, which flows throughout the region of Tuscany in north-central Italy. (Its route begins at Mt. Falterino, traverses several valleys and plains, and courses through Florence and Pisa, until it reaches the Ligurian Sea.) This sets them off on a rant about how terrible the cities and towns that border the Arno River are, and how beastly their citizens have become; the latter are compared to “ugly hogs” (42), “snarling curs” (46-47), “dogs turning into wolves” (50), and “foxes so full of fraud” (53). The choice of these four specific animals seems to come from The Consolation of Philosophy, where Boethius likens the lecherous to hogs, the quarrelsome to dogs, the avaricious to wolves, and the deceitful to foxes. It’s a stark warning about the dehumanizing effect of vice. Still … yikes!

As the conversation continues, Dante begs to know their names, and they graciously share with him what he refused them (yeah, it looks like he really did misread the moment). They are Guido del Duca and Rinieri da Calboli. In describing their life experiences, they reveal a couple of the ways that envy distorts humanity. For Guido, his psychological comparison with others had physiological effects: “My blood was so afire with envy that, if I saw a man becoming glad, you would have plainly seen me turn livid” (82-84). (In this case, the “livid” color in view is red). Conversely, Rinieri was better known for his active role in partisan rebellions and military campaigns; envy is also detrimental to politics and civil society at large. Together with others of their generation, they have much to regret, including the corruption of their families and the decline of civil courtesy more broadly. In the end, Guido dismisses Dante with a lament: “But go away, Tuscan; for I prefer to weep now than to speak, so much has our talk pressed heavily on my mind” (124-126).

As Dante and Virgil move on, they do not hear anyone else speak to them, but they take this as a sign that they are going the right way; otherwise, they trust, these courteous shades would redirect them. Suddenly, the silence is broken once again by invisible voices that accost them like a thunderclap after a flash of lightning. The first shouts, “Whoever finds me will kill me!” (133), alluding to the memory of Cain, who allowed his envy of his brother Abel to master him and incite him to commit fratricide. A second voice follows, “I am Aglauros, who became stone!” (139), invoking the myth of that unfortunate young woman who envied Mercury’s love for her sister. Once the calm has been restored, Virgil speaks for the first time in this canto to offer a summary evaluation: “That was the hard bit that should keep every man within his track. But you take the bait, so that hook of the ancient adversary draws you to himself, and therefore rein and lure do little good” (143-147). In quick succession, he has referenced three metaphors for discipline, which correspond to animals on land (a bit for a horse), in the sea (a hook for a fish), and in the sky (a lure for a falcon). For him, humanity’s disastrous failure to curb its earthly envy is what makes the pain of Purgatory so inevitable.

That’s all for now. In personal news, today is my 41st birthday. I guess that means that I’m no longer a young man “on the cusp” of middle age, but that I have decisively arrived there! Although in some ways I do still find myself lost in a dark wood, these past six months of journeying with Dante, Virgil, and all of you have been profoundly illuminating and truly life-giving. So thank you for joining me! For now, I’m off to reflect and celebrate, but I’ll be back on Saturday with Purgatorio Canto 15. I hope to see you then.

Yours on the journey,

Joshua

“Envy of Other People’s Poems” by Robert Hass (2007)

In one version of the legend the sirens couldn’t sing.

It was only a sailor’s story that they could.

So Odysseus, lashed to the mast, was harrowed

By a music that he didn’t hear—plungings of sea,

Wind-sheer, the off-shore hunger of the birds—

And the mute women gathering kelp for garden mulch,

Seeing him strain against the cordage, seeing

The awful longing in his eyes, are changed forever

On their rocky waste of island by their imagination

Of his imagination of the song they didn’t sing.

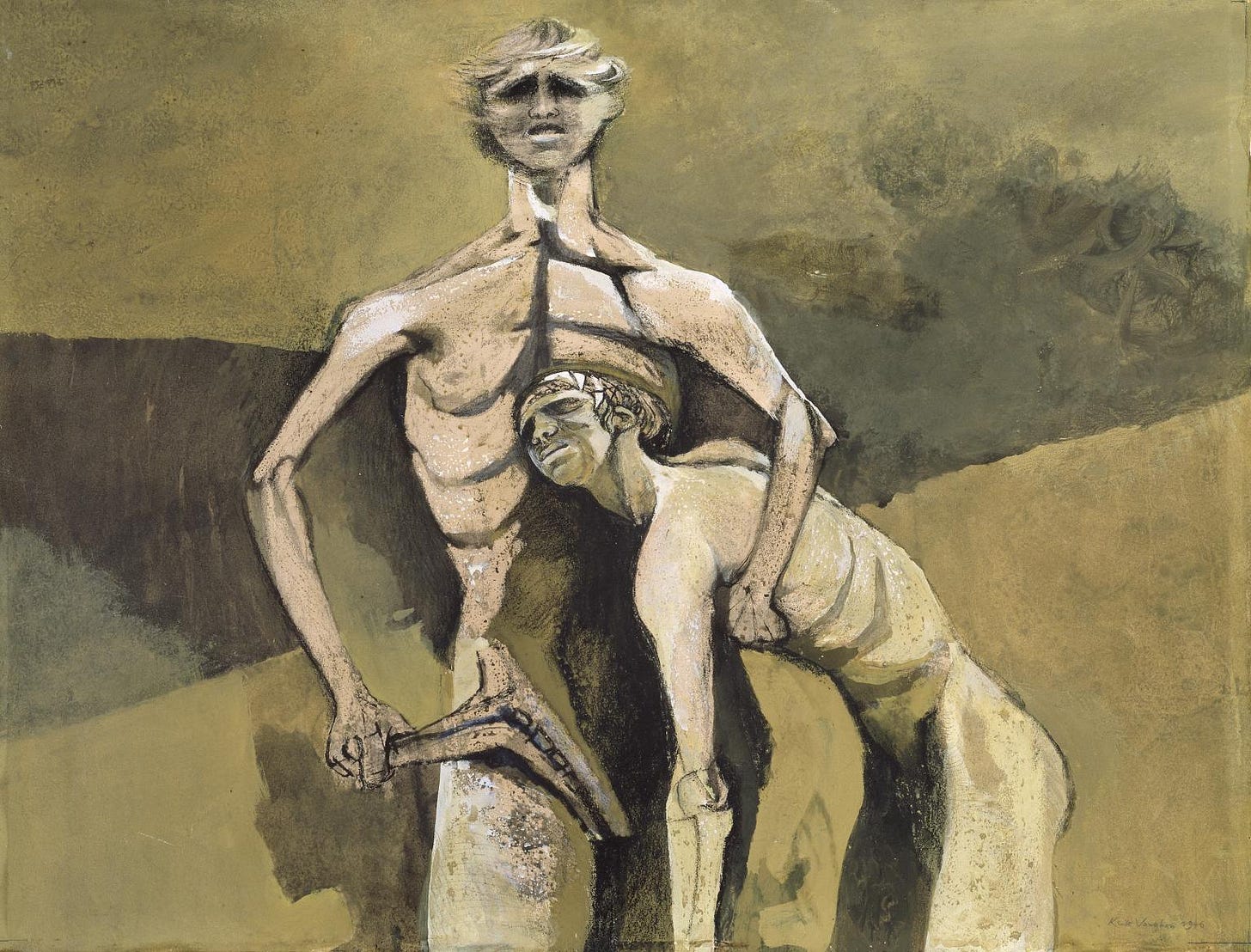

A map of interconnected emotions and experiences, including envy

Happy Birthday!